There is a curious note in the Crystal Palace Park guide; Geology and Inhabitants of the Ancient World1, about a series of footprints, which was installed with the extinct animal models in the Crystal Palace Park, in 1854. However, whereas the dinosaurian behemoths, such as the iconic Megalosaurus and Iguanodon, loom over captive audiences, and are impossible to miss, the footprints are nowhere to be seen....but perhaps we have found a clue…

Above: A series of footprints like these (Chirotherium) was supposedly installed in the Park2.

Above: A series of footprints like these (Chirotherium) was supposedly installed in the Park2.

Well, firstly, you might ask, who cares about footprints? In scientific circles today, fossil footprints are considered invaluable tools to unlocking secrets about the way extinct animals moved, behaved and interacted within their environment. They are essentially a window into the past. By the mid-19th century, the study of footprints was an exciting new frontier of palaeontology. Discoveries had recently come to light from Dumfriesshire, Scotland3; Hildburghausen, Germany4; Cheshire and Merseyside5 (UK) and the Connecticut Valley, US6. With so few bones and complete skeletons described worldwide at the time, footprint discoveries represented, in some cases, the only clues of the animals; the only real means by which the intangible past could become tangible; the only way we could make that connection to strange bygone eras and understand the seemingly invisible creatures7.

This Victorian fascination with fossil footprints was reflected in the large number of museum displays at the time; for instance, footprint slabs on display at the, then, British Museum galleries8 (now part of the Natural History Museum collection). Casts of footprint slabs were also available for purchase from Ward's 1866 Catalogue of Casts of Fossils9; there was clearly a demand to display and marvel at these natural curiosities.

Left: Image from Ward's (1866) Catalogue of Casts of Fossils, showing a cast of what is labelled as Chirotherium, on sale for $10.

So it's not surprising then that Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins would include footprints as part of his prehistoric landscape at Crystal Palace Park. Following the "sanction and approval" of the celebrated British anatomist, Richard Owen10, guiding the creative hand of Hawkins, these footprints (then, under the name of Cheirotherium) accompanied their presumed animal creators; three models of Labyrinthodon; essentially giant amphibians which Owen interpreted and described from fragmentary material in Warwickshire11.

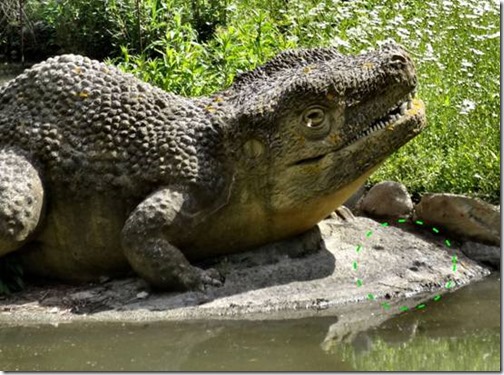

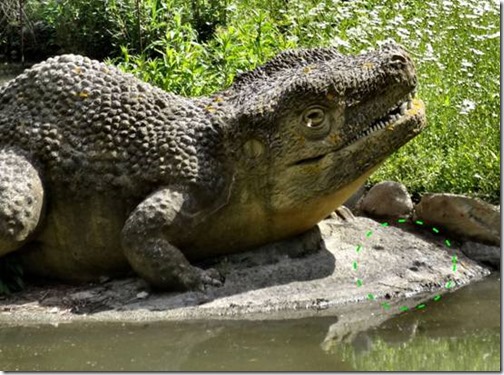

Above: The 'Labyrinthodons' are the first animal models which one discovers in the Park, if one works their way through the geological time sequence reconstructed by Hawkins (photograph taken in 2014).

So, where are the footprints now? I have spotted what we think may be the only surviving footprint, or pair of footprints12 in a photograph taken by Professor Joe Cain in 2013. However, strangely, I have only spotted it in just one photograph, and in numerous other photographs of the same models... well, it's just not there!

Above: Labyrinthodon with footprint, or pair of footprints, highlighted (taken in 2013)

Above: Photograph taken from same angle (2008): where is the footprint?

During a recent visit to the Park, I was still unable to spot the footprints, even using my binoculars and a powerful optical zoom camera (I could not get onto the islands without special permission from Park officials). Unfortunately, the spot has overgrown with plants, frustratingly obscuring any possible footprints.

It's well known to scientists who study footprints (known as ichnologists) that footprints can be highly elusive to the human eye. The slightest change in lighting, for instance, can unveil or shroud these prehistoric enigmas. This is because they are often of low relief and, paradoxically, if you're staring straight down at one...you could likely miss it.

The secret to spotting footprints, which any ichnologist will tell you, is to look for them when the sun is at a much lower angle, for instance, at daybreak or dusk. Then, get down as low as possible, and look across the surface (bedding plane) to spot the 'newly' emerging footprints.

We do know that our image was taken only in 2013, and no conservation work has been undertaken around the models since then. So it's possible that the footprint has been infilled with loose sediment or dirt. So we need to get out there with a brush....(under the watchful eyes of Rangers of course).

So, if you have had the fortune to visit the fantastic Crystal Palace Park, look at your photographs.... If you spot anything that looks like a footprint then tweet the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs at @cpdinosaurs or add a post on the Friends’ Facebook page. Or, if you happen to visit the Park again, don't just visit the dinosaurs....give the 'Labyrinthodons' some of your time; start footprint spotting....

"There is no branch of detective science which is so important and so much neglected, as the art of tracing footsteps" — Sherlock Holmes, A Study in Scarlet.

(Note: I have posted a virtually identical piece earlier on the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs website).

References and Notes

1 Owen, R, and Hawkins, B. W. (1854). Geology and Inhabitants of the Ancient World. Crystal Palace Library. 39 p.

2 From Kaup, J. J. (1835). Das Tierreich 1. Johann Philipp Diehl, Darmstadt: 116 p.

3 Duncan, H (1831) An Account of the Tracks and Footprints of Animals Found Impressed on Sandstone in the Quarry of Corncockle Muir in Dumfriesshire. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh,11:194-209.

4 Kaup, J. J. (1835). Mitteilung über Tierfährten von Hildburghausen. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie, 1835:327–328.

5 Cunningham, J. (1838) An Account of the Footsteps of the Chirotherium and Other Unknown Animals Lately Discovered in the Quarries of Storeton Hill, in the Peninsular of Wirrall between the Mersey and the Dee. Proceedings of the Geological Society of London, 3: 12-14.

6 Hitchcock, E. (1836) Ornithichnology-Description of the Footmarks of Birds, (Ornithichnites) On New Red Sandstone in Massachusetts. American Journal of Science, Series 1. 29:307-340.

7 For an example of how footprint evidence may be the only proof of an animal's existence, in the geological record, see Tresise, G. R. (1989) The Invisible Dinosaur. National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside. Eaton Press, Wallasey, Merseyside. 32 p.

8 Mantell, G. A. (1851) Petrifactions and Their Teachings; or, a Handbook to the Gallery of Organic Remains of the British Museum. Henry G Bohn, London.

9 Ward, H. A. (1866). Catalogue of Casts of Fossils: From the Principal Museums of Europe and America, with Short Descriptions and Illustrations. Benton & Andrews, printers.

10 Hawkins, B. W. (1854). On Visual Education As Applied to Geology. Journal of the Society of Arts, 2: 444-449.

11 Although Cheirotherium is the correct spelling in Greek for hand beast, Chirotherium (the incorrect spelling) was used first and therefore, under the provisions of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, is the valid name, used now. It is now thought that this type of footprint was made by animals more closely related to crocodiles, than to amphibians (see Tresise 1989, above for more details).

12 There is a short note in McCarthy and Gilbert (1994) (full reference below) that one of these footprints still survives.

McCarthy, S. and Gilbert, M. (1994) The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs: The Story of the World's First Prehistoric Sculptures. Crystal Palace Foundation.