In most sea urchins (such as the regular sea urchins), the mouth is on the bottom side of the body, whereas the anus is on the upper surface. This is an excellent adaptation to living on the seafloor, so that the mouth is in contact with the substrate, enabling it to graze on algae and detritus. Some species, such as the European Edible Sea Urchin (Echinus esculentus), a North Atlantic species, are omnivorous and feed on both sponges and bryozoa, in addition to seaweed.

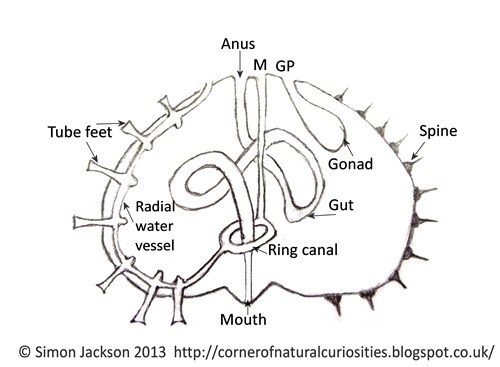

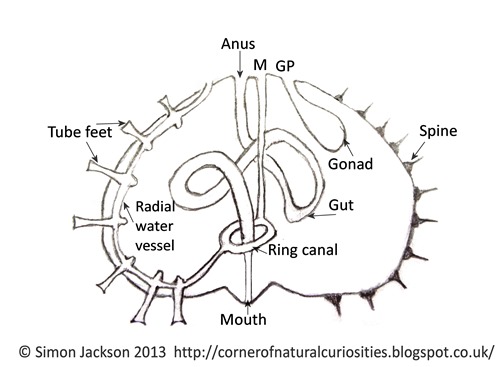

In these regular sea urchins, the mouth consists of a complex feeding mechanism (known as Aristotle's lantern) which consists of five strong jaws, each with a single tooth of the mineral calcite. After food has been grasped by the apparatus, it is then passed up through a complexly coiled gut, and the waste is passed upward through the anus.

Above: a simplified vertical cross-section through a regular sea urchin, showing the digestive organs. (M = madreporite; GP = genital pore).

In heart urchins and sand dollars (irregular sea urchins) there is a distinct front and back (due to their bilateral symmetry). The mouth is still on the lower surface, though it is nearer the front, and the anus is nearer the back end.

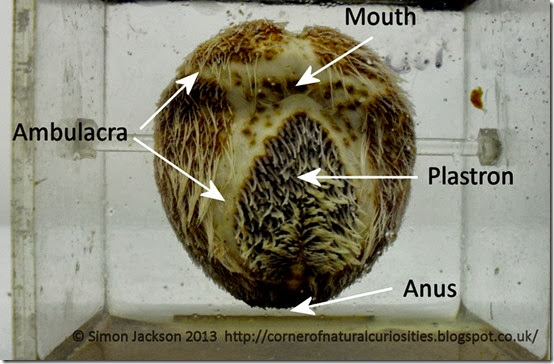

Above: specimen of heart urchin (Echinocardium), showing its lower surface, including mouth and anus (Courtesy of UCL, Grant Museum of Zoology_specimen NON2391)

Sand dollars have short spines which move the sand and organic debris over their upper surfaces and into their mouths — allowing the sea urchins to 'sieve' through the substrate surface for food.

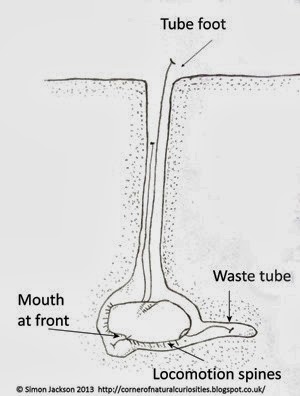

Heart urchins, living 10 cm or deeper within burrows, beat tiny hairs (cilia) on their spines to draw in currents of water, containing small particles of food. These currents also help to wash the faecal waste along a specialised sanitary pipe, at the back of the burrow.

Above: simplified cross-section through a burrow of Echinocardium. Note the long tube feet above and behind the urchin which are used to construct parts of the burrow. Smaller sticky tube feet, at the front of the urchin, catch food particles and pass them to the mouth.

Read also:

What Are Sea Urchins?

What Are the Main Types of Sea Urchin?

How Do Sea Urchins Move?

How Do Sea Urchins Reproduce and Grow?

Where Do Sea Urchins Live?