There are two types of sea urchin: regular and irregular urchins.

Regular sea urchins (regular echinoids) are more common. Regular echinoids are radially symmetrical (a vertical cut from one side of the animal to the other, across the centre, in two or more places will produce two halves that are mirror images of each other). These sea urchins are hemispherical in shape (crudely resembling the top half of a sphere). There is no front or back and these urchins can move equally easily in all directions.

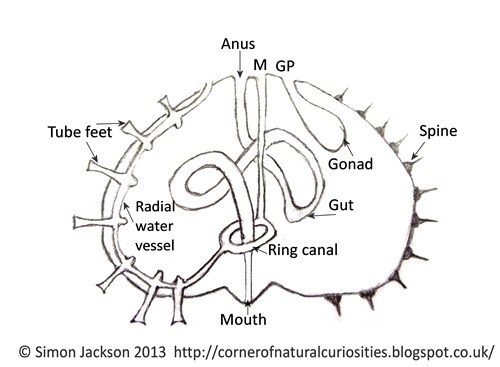

Other key features include: an anus which is in the centre of an urchin’s upper surface; a mouth which is in the centre of its lower surface; and long, pronounced spines.

Regular sea urchins live on the surface of the seabed and graze on seaweed.

Above: a specimen of Echinus esculentus, with spines removed, showing key features of sea urchins as seen on upper surface (Courtesy of UCL, Grant Museum of Zoology_specimen S174).

Above: a specimen of Echinus esculentus, with spines, showing mouth (with Aristotle's Lantern) on lower surface (Courtesy of UCL, Grant Museum of Zoology_specimen S251).

Irregular sea urchins, or irregular echinoids, include the sand dollars and heart urchins. These have a distinct front and back, because of their bilateral symmetry (only one vertical cut, from front to back, through the centre, will produce two halves which are mirror images of each other).

In sand dollars, the mouth is still on the lower surface, and is either central or nearer the front. The position of the anus is variable, but is nearer the back end. In heart urchins (e.g. Echinocardium), the anus is right at the back of the urchin, whereas the mouth is near the front.

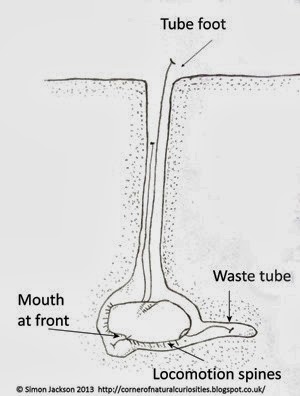

Irregular sea urchins have a flattened body, and either live partly or completely buried in soft sediment, such as sand. Heart urchins live in burrows within the sediment, using secreted mucus to stabilise it. Specialised tiny beating projections (cilia) on the spines draw in currents of water, containing fresh oxygen, for respiration, and food particles.

Above: specimen of Echinocardium, showing its upper surface (Courtesy of UCL, Grant Museum of Zoology_specimen NON2391)

Above: specimen of Echinocardium, showing its lower surface (Courtesy of UCL, Grant Museum of Zoology_specimen NON2391)

(Note that some people constrain the term "sea urchins" to the regular echinoids, but usage here of the term "sea urchins" also includes irregular urchins (sand dollars and heart urchins) — a usage which broadly follows the Natural History Museum Echinoid Directory).

Read more:

What Are Sea Urchins?

How and What Do Sea Urchins Eat?

How Do Sea Urchins Move?

How Do Sea Urchins Reproduce and Grow?

Where Do Sea Urchins Live?