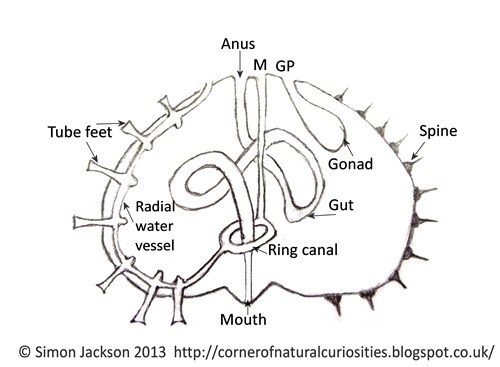

Most sea urchins (particularly regular sea urchins) move using their tube feet. These are tube-like projections, extending from their body (from the star-shaped ambulacral regions), which end in sucker-like projections.

Tube feet are extensions of a complex set of canals within each sea urchin — a water-vascular system. Each tube foot can be extended when the urchin pumps fluid into it, allowing the foot to reach out. The suction cup, at the end of each small foot, sticks to an object, or an adjacent part of the seafloor. The sea urchin is then pulled towards the object, as the feet contract, when the water pressure within them is decreased.

In regular urchin species, such as Echinus esculentus, the tube feet allows the animal to grip onto rocks, within turbulent marine zones (down to depths of about 50 m), so that it is not detached by waves. It is able to climb steep rocks and, being radially symmetrical, it is well adapted to moving equally well in all directions.

This method of locomotion — hydraulic powered tube feet — is unique to sea urchins and other echinoderms (which also includes starfish, sea cucumbers, sea lilies and brittle stars).

Above: a simplified vertical cross-section through a regular sea urchin, showing the tube feet (M = madreporite; GP = genital pore)

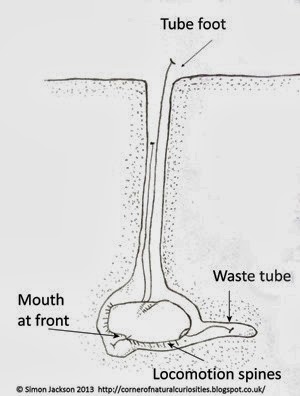

Irregular sea urchins, such as sand dollars and heart urchins, are adapted to moving in a different environment. They move using their small, almost fur-like covering of spines, rather than tube feet. Irregular sea urchins have a distinct front and back end (being bilaterally symmetrical) and they use their lower (oral) spines to move only in a forwards direction. The urchin, Echinocardium uses it spines in a 'rowing' motion to move forwards within its burrow.

Read more:

What Are Sea Urchins?

What Are the Main Types of Sea Urchin?

How and What Do Sea Urchins Eat?

How Do Sea Urchins Reproduce and Grow?

Where Do Sea Urchins Live?