Sea urchins, or echinoids, are small, seafloor dwelling invertebrates (they have no backbones), that are spiky, often brightly coloured and either globular (e.g. the edible sea urchin), disc-shaped (e.g. sand dollars) or heart-shaped (e.g. heart urchins). There are over 900 living species, with an evolutionary history that stretches back 450 million years.

Above; Fragile pink sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus fragilis) live in communal groups off the west coast of North America. (Picture courtesy of all-free-download.com)

Sea urchins, comprise the class Echinoidea and are echinoderms, a group which also includes starfish, brittle stars, sea cucumbers and sea lilies. A familiar feature of echinoderms, particularly the sea urchins, is their spines or sharp projections — a feature which many unwary swimmers are painfully familiar with (Echinodermata is derived from the Greek and Latin for 'prickly skin').

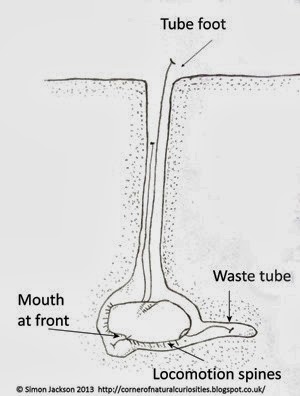

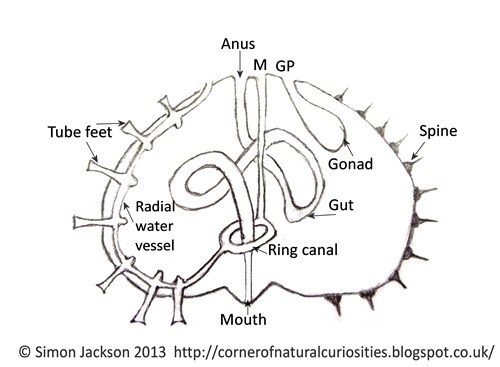

The spines of a sea urchin connect via tubercles to its rigid skeleton (known as a test). In most species, the test is circular when viewed from above, with the anus on top, and the mouth at the bottom (do sea urchins feed through their bottoms?)

Unlike starfish, sea urchins lack arms. However, the test of a sea urchin consists of a series of plates which are arranged into pairs of columns, or 'bands', which radiate outward from the top (apex) of the skeleton and have a star-shaped configuration.

Five of the star-shaped 'bands' (termed ambulacra) bear tiny pores. Through each pore, a tube-like structure extends, each one ending in a circular disc — these are called tube feet, and a sea urchin can move them, by controlling the pressure of water within them. This system, unique to sea urchins and other echinoderms, allows a sea urchin to move, feed and in some species, respire.

Above: a specimen of Echinus esculentus, with spines removed, showing key features of sea urchins (Courtesy of UCL, Grant Museum of Zoology_specimen S174).

In addition to spines and tube feet, a sea urchin possesses tiny pincer-like structures (pedicellariae). These help to keep it clean and to avoid parasites (such as marine larvae settling on it). Many species of sea urchin also bear venom glands, within pedicellariae, which can be used to ward off predators or subdue prey.

In summary, a sea urchin can be thought of as a small rounded ‘box’, consisting of many small plates connected together, which uses its specialised projections (spines, tube feet, pedicellariae) to interact with its environment.

You may like to read:

What Are the Main Types of Sea Urchin?

How and What Do Sea Urchins Eat?

How Do Sea Urchins Move?

How Do Sea Urchins Reproduce and Grow?

Where Do Sea Urchins Live?